If you can’t give me poetry, can’t you give me poetical science? – Lady Ada Lovelace

Editing poems for potential inclusion on the blog this week led me to reflect on the connection between my professional life and my creative life, and the ancestors to whom I owe that connection.

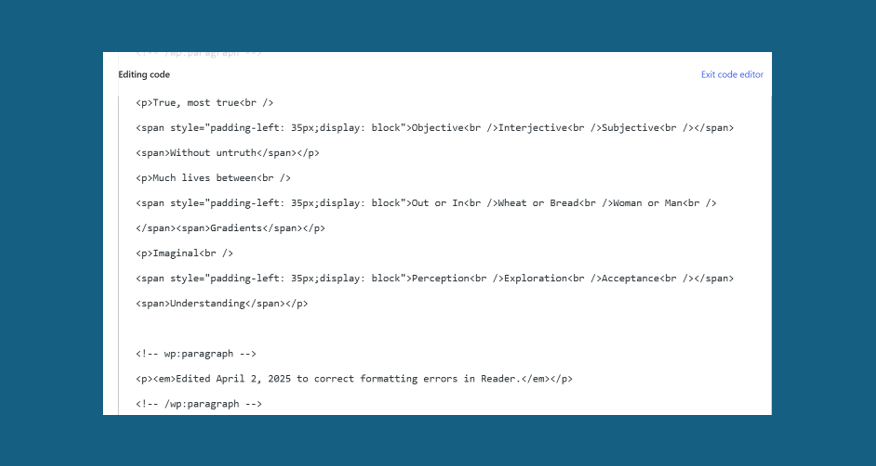

WordPress’s default editor gets on my nerves. I find the whole user interface counterintuitive and inconducive to arranging poetry how I want. However, I can usually achieve what I want using the code editor. Computer code uses a series of symbols, letters, and numbers in formulaic fashion to tell webpages exactly how content should appear. The featured image on this post illustrates what I mean. I essentially translate each poem into the language of computer programming before I bring it to WordPress. This is a habit I developed in my “day job” as an instructional systems designer creating online training courses.

Here I mainly use code to help WordPress blocks understand the difference between a paragraph break (</p>) and a line break (<br>). For my poem “Three Suggestions” a few weeks ago, I got a little fancier and used code for indenting lines without indenting the paragraph (<span style=”padding-left: 35;display:block”>). These codes do not visually appear in the final post, but their affects are integral to the content’s behavior. In this way, the code is deeply woven into the poem’s form. In fact, this is true of every poem posted anywhere on the internet. Webpages can’t function without code anymore than human skin cells can function without DNA. Even if we use the simplified editor that lets us just type words and press buttons to insert images, all that really means is that there’s software doing the coding for us automatically. Coding is still happening, and code still defines our content’s final appearance.

The roots of this creative process go back to Our Mother of Computing herself, Lady Ada Lovelace. Ada was the daughter of infamous romantic poet Lord Byron and Anne Isabella Milbanke, a student of mathematics (among other pursuits). As an adult, Lady Lovelace worked with Charles Babbage on his Analytical Engine, the steam-age precursor to modern computers. In so doing, Lady Lovelace became the first computer programmer and laid the foundations for inventions that would one day (for better or worse) redefine the human existence.

Her work expressed her quest to blend the poetic nature inherited from her father with the mathematical prowess fostered by her mother. Consider how the number and stress of syllables in a poem defines its form. The same applies to computer code; the deliberate arrangement of characters defines the page’s form. Ghazals and villanelles become such through the patterns they follow; code relies on patterns to mark the boundaries of specific functions. Lady Lovelace’s ability to see the relationships between numbers as rhymes and meters, combined with her ability to imagine new possibilities and express them through metaphor, enabled her to reach far beyond her own time and give us the keys to new worlds of discovery.

I can’t type code for poems without thinking of her. This is the realization of the integration she worked for: the programming inside the poem; the poem inside the programming. I’d like to think she’d be pleased.

Leave a comment